Positive Illusions: The Psychology of Self-Enhancement

Most people are around average or worse, but few of them believe that.

In their 1988 article “Illusion and Well-Being,” Shelley E. Taylor and Jonathon D. Brown proposed a radically novel theory of mental health that psychologists are still debating today. Whereas previously psychologists had viewed accurate perception of reality as a defining feature of mental health, Taylor and Brown argued that mental health depended on positive illusions. Normal, mentally healthy people did not perceive and reason about the world in an unbiased manner. Rather, their reasoning was characterized by “incomplete data gathering, shortcuts, errors, and biases” that resulted in unrealistically positive, or self-enhancing, evaluations of themselves.

Taylor and Brown identified three fundamental illusions that were essential to mental health: unrealistically positive views of the self, unrealistic optimism, and the illusion of control. Normal people tend to view themselves and their futures more positively than an unbiased observer would. They also exaggerate how much control they have over the world.

Taylor and Brown went on to maintain that, compared to realists, self-enhancers are happier, better able to cope with adversity, more popular, more caring of others, and more motivated to tackle and persist at difficult tasks. They even made the shocking claim that a realistic view of oneself is a symptom of depression. Taylor’s subsequent work on AIDS patients suggested that positive illusions even improved physical health outcomes.

In the following decades, positive illusions became a central topic in social psychology, with most work confirming Taylor and Brown’s original thesis. In 2005, David Dunning, of “Dunning-Kruger effect” fame, synthesized work on the nature and causes of positive illusions in his book Self-Insight: Roadblocks and Detours on the Path to Knowing Thyself. This remains the best overall account of positive illusions, and I highly recommend it to anyone who wishes to achieve self-knowledge. I have drawn heavily on this book for this essay, but I have supplemented my account with more recent work on positive illusions.

I will deal here only with the first part of Taylor and Brown’s thesis: that positive illusions are integral to psychological normality. This part of the thesis has been massively supported by subsequent research and is less controversial than the claim that these illusions lead to well-being, which I address here.

Unrealistically positive views of the self

Taylor and Brown’s first contention is that people normally hold unrealistically positive views of themselves. What is the evidence for this?

The better than average effect

The first line of evidence is the “better than average effect,” also known as the “Lake Wobegon effect.” If people were accurate in their self-assessments, you would expect them to be about equally likely to rate themselves as below and above average on personality traits and abilities. But this is not at all what has been found. Rather, majorities, often large ones, rate themselves above average for positive traits, and minorities below average. The reverse is true for negative traits. The effect is often quite large.

Dunning cites examples of this effect on a wide array of traits. A survey of high school seniors found that 60% of them rated themselves as above average in athletic abilities and only 6% as below average. 94% of professors view themselves as doing above-average work compared to their peers. People think that they are less susceptible to the flu than average. Bungee jumpers think that they are less likely to meet with harm than the typical bungee jumper (their families disagree!).1

There is no sign that the better than average effect has diminished in recent years. For example, a 2018 study asked US Air Force Academy cadets to rate their leadership skills compared to their fellow cadets on a scale of 0 to 99. The average rating was 80, significantly above the 50 that would be expected if the cadets had been unbiased. Only 3 cadets out of 251 rated themselves below average. A 2020 meta-analysis reviewed 124 studies of the better than average effect and found a robust total effect.

Objective vs. subjective measures of traits

Another way of testing for self-enhancement is to compare people’s estimates of their abilities with objective measures of that ability. You could ask someone what they thought their IQ was and then give them an IQ test or compare an athlete’s rating of their sports ability with a coach’s standardized assessment.

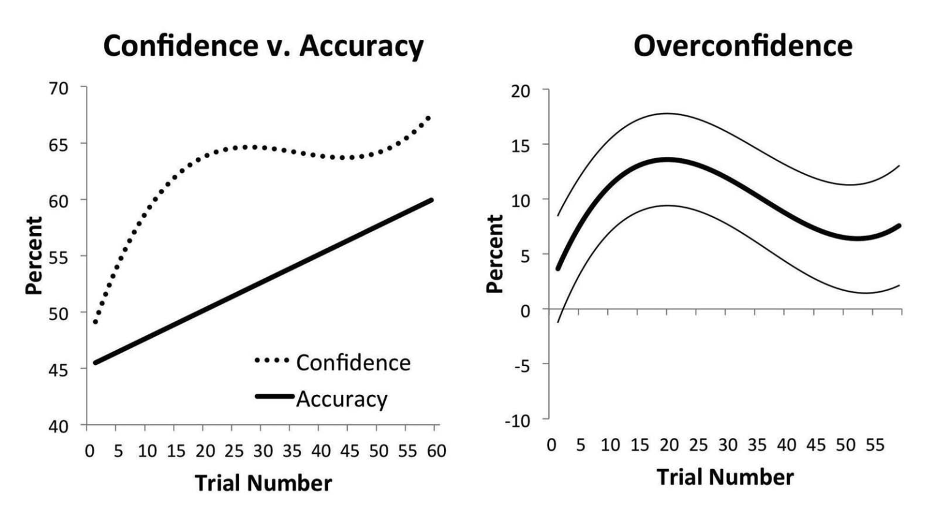

The famous Dunning-Kruger effect is relevant here. Justin Kruger and Dunning found that people with low skills in humor, logical reasoning, and English grammar were dramatically overconfident in their estimates of how well they performed on objective tests of these skills. This study found that a minority of the most highly skilled subjects accurately assessed, and even underestimated, their abilities relative to others. More recent research by Carmen Sanchez and Dunning found across an array of tasks that, while overconfidence was particularly high among those with low skills, subjects at almost all skill levels were overconfident in their performance. Overconfidence was lowest or absent among people who had no knowledge at all of the subject being tested. As they gained more knowledge, they rapidly became overconfident in their abilities. Overconfidence diminished as subjects gained more knowledge but never disappeared and even spiked once again among the most knowledgeable subjects (see graph).

A 2014 meta-analysis that examined measures of a wide array of traits, including academic, sports, and memory ability, found a correlation of only 0.29 between subjective and objective ratings, meaning that self-rating accounts for less than 10% of actual ability. This effect is mainly due to overestimates of ability. Self-ratings tended to be more accurate to the extent that the rated abilities involved tasks that were familiar, low in complexity, and amenable to exact measurement.

Comparisons between expected and actual performance

A particularly effective way of demonstrating self-enhancement is to compare subjects’ predictions of their performance with their actual performance. Nicholas Epley and Dunning surveyed Cornell University students about their likelihood of buying flowers to fund cancer research at a “Daffodil Day” event that was held regularly at the university. The survey occurred five weeks before Daffodil Day. 83% of students predicted that they would buy at least one daffodil. As it turned out, only 43% of students bought flowers. The students had exaggerated their charity and altruism.

Another study asked subjects with college degrees to rate how well they could explain topics relating to their majors. They were then instructed to write out an explanation of those topics and rerate their ability. The second ratings were significantly lower than the first, meaning the subjects had overestimated their expertise.

The Illusion of Control

The illusion of control gives people the belief that they can control events that they cannot. Gambling behavior provides many excellent examples of this illusion. People believe that they have a higher probability of winning a coin toss if they themselves toss the coin rather than someone else. They are more likely to bet on a roll of a die if the die has yet to be thrown than if it already has. They also throw the dice harder if they need a high number. People believe that they are more likely to win a lottery if they pick which ticket they get or choose the numbers themselves. They believe that they are more likely to win at a game of chance when their opponent is nervous and awkward than when he is attractive and confident. Gamblers believe that there is a property of luck that is independent of skill and chance that is inherent to individuals, like hair color or height. Successful gamblers, on this theory, are successful because they have this property of luck that enables them to control the outcome of games of chance. Gamblers rate luck as being the most important component of gambling success above skill and chance.2

The illusion of control is also visible in other contexts. We saw above that people tend to overestimate their positive traits. This overestimation is particularly large for traits that people can control. People see themselves as slightly superior on traits that they cannot control, like intelligence, but much more superior on qualities like cooperativeness and politeness, which are in their control. This discrepancy implies that people believe that they have extraordinary powers to make their behavior conform to an ideal.

People also believe that they are likely to experience better outcomes when they, rather than someone else, are in control. They believe that they are less likely to have an accident when they, rather than someone else, are driving a car. This belief applies specifically to the aspects of driving that a driver controls, like changing lanes or turning sharply, but not to uncontrollable dangers like brake failure or tire punctures.3

A 2014 meta-analysis of 20 studies of the illusion of control found a significant effect across the studies.

Unrealistic optimism

Unrealistic optimism is related to the unrealistically positive view of self. Just as people overestimate their positive qualities, they overestimate their efficacity and chances for success in the future.

One particularly pervasive form of unrealistic optimism is the planning fallacy. When planning projects, people dramatically underestimate the time, effort, and cost required to complete them. Public construction projects are notorious for time and cost overruns. Roger Buelher and his colleagues give the construction of the Sydney Opera House as an example: “According to original estimates in 1957, the opera house would be completed early in 1963 for $7 million. A scaled-down version of the opera house finally opened in 1973 at a cost of $102 million.” Buelher et al. go on to show that the planning fallacy also applies to everyday tasks. College student subjects underestimated the amount of time that it would take them to complete their theses and coursework, as well as non-academic tasks like fixing a bicycle and writing a letter to a friend.

A wonderful 2013 survey is filled with examples of unrealistic optimism from the massive literature on the subject. University students are unrealistically optimistic about the grades that they will receive and their starting salary after graduation. People’s assessments of the likelihood of negative events, like heart attacks and breast cancer, are much more optimistic than objective measures indicate. The better than average effect also applies to predictions of the future. People on average believe that they are less likely than average to experience negative life events, like getting fired, being sued, developing asthma, or suffering from food poisoning.

How we maintain positive illusions

The evidence that positive illusions are integral to psychological normality is overwhelming. But how do people maintain these illusions? People believe that they are seeing self and reality in an unbiased manner, but, beneath the threshold of consciousness, perceptions are filtered to yield an enhanced self-image. Dunning and other psychologists have outlined a number of social and cognitive mechanisms through which we filter reality to maintain our illusions.

The first is biased feedback from others. People dislike criticizing others and often distort or withhold negative opinions about them, which results in a positively biased self-perception. For example, in an experiment where subjects were asked to play the role of supervisor and evaluate the work of subordinates, they gave much higher ratings to subordinates when they knew that the subordinates would see the ratings, as opposed to when they were told ratings would be private. In another experiment, subjects evaluated paintings and were asked to discuss the ones that they liked the best and least with someone posing as the artist. Subjects dwelled on the aspects of the paintings that they liked, but failed to mention or minimized the aspects that they liked the least. When they liked a painting, they pointed out many more aspects of it that they liked than disliked. However, when they disliked a painting, they pointed out almost as many liked aspects as disliked aspects. Subjects sometimes expressed their negative opinion indirectly. When discussing a painting they disliked with the artist, they would talk about how much they disliked the work of other artists, while not mentioning the painting under discussion explicitly. People also seek out feedback that confirms their self-image and try to elicit such feedback from others.

People also devote different amounts of scrutiny to positive and negative feedback. As Dunning says:

When they receive positive feedback, they accept it at face value without much protest. However, when people receive negative feedback, they pull out their psychic magnifying glass and give it a good stare, looking for ways they can discount or dismiss it.4

For example, when psychologists diagnose subjects as testing positive or negative for a fictional health risk, the subjects with the positive diagnosis are much more likely to scrutinize its accuracy.

People’s self-concept is also biased by how they interpret their own actions. They believe that actions that confirm their self-image reflect central and durable aspects of the self, whereas disconfirming actions are fleeting and isolated. They use abstract language when referring to their positive behaviors and concrete language for negative behaviors.5 If they donated money, they say, “I was charitable,” but if they slapped someone out of anger, they don’t say “I was hostile.” Rather, they just describe the concrete action. When asked to describe a situation that made them angry, subjects tended to describe a long series of provocations that was still ongoing in the present. However, when asked to describe a situation in which they angered others, they say that the anger was caused by a brief, uncharacteristic episode that had no relevance to current circumstances.

Hundreds of studies have found that people attribute positive outcomes to themselves and negative outcomes to other causes, a phenomenon known as “the self-serving bias.” A classic analysis of sports journalism found that baseball teams attribute their wins to superior ability and effort, but losses to external factors, like weather and bad luck.

Another psychological mechanism that supports self-enhancement is our memory. We find it easier to recall memories that are consistent with our self-image, and, since most people’s self-image is positive, they are more likely to recall positive than negative memories and more likely to overestimate how happy they were in the past.

People also enhance their self-images through self-serving trait definitions. Desirable traits like intelligence, leadership ability, and creativity are vague and ambiguous, so they can be defined in many ways. People tend to view their own traits as central to the definitions of positive vague qualities, but irrelevant to those of negative vague qualities. People who are good at math tend to view math ability as central to the definition of intelligence, whereas people who are more intuitive than logical are less likely to view logical ability as central. The reverse applies to negative vague traits like submissiveness and aloofness. Accordingly, the better than average effect is very high for vague traits, but much lower or even absent for narrowly defined traits like punctuality. The better than average effect disappears when people are made to self-evaluate according to someone else’s definition of vague positive qualities like intelligence.

Another source of bias is people’s use of internal rather than external assessments of themselves. If I want to judge how likely a newlywed friend is to get divorced, I can go about deciding in two ways. I can evaluate her personality traits and judge the matter based on them. Is she likely to be faithful? Is she crazy? This is the case-based or internal method of evaluation. The other way is to seek statistical information. If she is a white American woman in her 30s, I can consult scientific sources that estimate her likelihood of divorce. If the likelihood is 30%, I can use this information as the basis for my prediction. This is the distributional or external method of evaluation.

Dunning notes that humans are quite good at gathering distributional information. To return to the Daffodil Day experiment described above, 83% students predicted that they would be altruistic enough to buy a daffodil, but they predicted that only 56% of other students would buy them. In reality, 43% of students bought daffodils, which was fairly close to students’ estimate of what other students would do. If students had based their estimate of their own behavior on distributional information, they would have gotten much closer to the truth. However, when people evaluate themselves, they typically ignore distributional information and use only the internal method. In other words, people think that the statistics apply to others and not to themselves.

Do illusions lead to well-being?

I have dealt here with one half of Taylor and Brown’s original thesis: positive illusions are integral to normal human psychology. However, I have not addressed the second half: that these illusions contribute to well-being. Do our illusions really make us happier, more popular, and healthier? Is it really true that depressed people tend to have a more realistic self-image than mentally healthy people? Are narcissists, who self-enhance to an extreme degree, really happy? Do unrealistic optimism and the illusion of control cause us to take potentially disastrous risks? And what about the effects of our illusions on other people? Do others suffer from our own self-enhancement? I hope to start digging into these questions soon.

Dunning, D. (2021). Self-insight: Roadblocks and detours on the path to knowing thyself. Routledge, p. 6. This is a reprint of a book that was originally published in 2005 by Psychology Press. I have relied on the book throughout. Where possible, I have supported my points through links to full-text articles, but where none were available, I give references to the Dunning book.

Dunning, pp. 85-86.

Dunning, pp. 82-83.

Dunning, p. 74.

Dunning, p. 75.

The positive illusion effect is definitely real— most drivers think they're above average etc.— but I think that there's a little more going on in this particular example:

"For example, a 2018 study asked US Air Force Academy cadets to rate their leadership skills compared to their fellow cadets on a scale of 0 to 99. The average rating was 80, significantly above the 50 that would be expected if the cadets had been unbiased."

My intuition is that 17 year old air cadets are probably more egotistical than average. As the paper cited suggests: "Inflated leadership ability self-assessment might also be associated with dark-side personality traits related to narcissism". But also, although the study would have been anonymised, I wouldn't necessarily expect a teenager in the military to feel fully assured that the results wouldn't be seen by commanding officers, which could lead to more boosterish self-reporting.