Why is Christianity such a popular belief system? There are undoubtedly many reasons. Some people may benefit from the moral structure that Christianity provides, and others may benefit socially from belonging to a congregation. However, one of the most powerful motivators of belief is that it directly causes positive emotions. As the evangelical preacher Billy Graham wrote:

You will never be free from discouragement and despondency until you have been tuned to God. Christ is the wellspring of happiness. He is the fountainhead of joy. Here is the Christian’s secret of joy.

Christian belief commonly has an anti-depressant and invigorating effect. But how does it produce this effect, and what is its nature?

In “Are Illusions Good for You?” I made the case that one source of self-esteem and psychological well-being is positive, self-enhancing illusions. Normal human psychology is characterized by unrealistically positive views of the self, the illusion of control, and unrealistic optimism. Elsewhere, I argued that people also need to believe that they are unique and overestimate their uniqueness. Positive illusions are self-esteem boosters that result in ability to cope with adversity, high motivation, and other emotional benefits.

Christians believe that their religion spread through the workings of God. However, to a religious skeptic like myself, it seems that there might be a more natural explanation for the popularity of this religion: it tends to strengthen positive illusions. Several lines of evidence support this positive illusions theory of Christianity. First, Christian doctrine seems designed to instill optimism, a sense of control, and the other positive illusions. Also, Christian belief and positive illusions have similar psychological outcomes. Just as positive illusions protect people from depression, for example, so does Christian belief.

Finally, there is growing evidence that Christian religiosity predicts high self-enhancement. I will review research that finds Christians tend to be dishonest with themselves and others and have a grandiose self-image.

I should be clear that I do not think that these self-enhancing effects are unique to Christianity. Very likely, boosting believers’ self-image is a function of many religions. I focus on Christianity because it has been far more extensively studied by scientists than any other religion has.

Christian doctrine and positive illusions

Christian doctrine intuitively seems tailor-made to boost positive illusions. I will use Pastor Rick Warren’s The Purpose-Driven Life1 as my guide to contemporary Christian doctrine. Originally published in 2002, this book has sold more than 50 million copies, making it one of the best-selling non-fiction books of all time. Its popularity means that it ought to be representative of contemporary Christian belief.

Warren’s thesis is that God has a unique purpose for all of us: “You were born by his purpose and for his purpose” (21). Our individual purpose “fits into a much larger, cosmic purpose that God has designed for eternity” (25). God’s purpose provides us with motivation and passion: “Purpose always produces passion” (36).

Such purpose gives people hope. Warren quotes Jeremiah: “I have good plans for you, not plans to hurt you. I will give you hope and a good future” (35). Since God has a purpose for us, we can be optimistic that we will succeed at life if we obey God. Besides, we can be optimistic about what comes after this life: we will receive an eternal reward after death if we fulfill God’s purpose.

God does not guarantee us happiness in this life, and, indeed, we will experience “a significant amount of discontent and dissatisfaction” (52). However, even if we suffer, we will feel fulfillment and satisfaction if we accept God’s purpose for us.

It feels good to do what God made you to do. When you minister in a manner consistent with the personality God gave you, you experience fulfillment, satisfaction, and fruitfulness. (244)

We have been made with unique attributes in order to fulfill our unique purpose.

You are God’s handcrafted work of art. You are not an assembly-line product, mass produced without thought. You are a custom-designed, one-of-a-kind, original masterpiece. (233)

God makes us “wonderfully complex” and gives us special “abilities, interests, talents, gifts, personality” to fulfill his purpose (233).

It’s not hard to see how this doctrine would boost the positive illusions of Christians.

Unrealistically positive views of the self and the need for uniqueness. People need to see themselves as unique, and they consequently overestimate their abilities and positive character traits. What Warren says seems designed to encourage such an inflated self-image. He tells Christians that God has given them special abilities that enable them to do something important that no one else can. To a skeptic like myself, this claim seems highly dubious. Most people are around average on most traits, and it’s unlikely that other people couldn’t do their life’s work as well as they could. Warren also tells Christians that each of them is a “one-of-a-kind original, masterpiece.” This belief protects us from the deflating notion that we might be average in most or all respects.

The illusion of control. As Warren portrays him, God is not cruel and would never place us in a world that we couldn’t control. Rather, we have all the control that we need to accomplish our purpose, which is the point of our lives. What more control could we want?

Unrealistic optimism. No matter how badly our lives go, it will all turn out fine if we accept God’s purpose for us. Not only will we experience eternal bliss after death, but we will feel fulfilled and satisfied here on earth.

The psychological benefits of Christian belief

If Christian doctrine is designed to bolster our positive illusions, you would expect that Christianity and positive illusions would have similar effects. Positive illusions protect against depression and promote psychological well-being, self-esteem, high motivation, and high ability to cope with adverse life events. Does Christian belief do the same?

The psychologist Harold G. Koenig has established that Christianity does indeed have these effects. He reviewed 3,300 studies of the psychological and physical outcomes of religious belief. The large majority of these studies used Christian subjects. He found that religious belief was associated with effective coping with adversity, psychological well-being, low rates of depression, optimism, and other positive traits.

Koenig also found that Christians are high in self-esteem. Christians’ high opinion of themselves might seem at odds with the Christian doctrine that humility is required for salvation and blessedness. As Saint Paul said, “Do nothing out of selfish ambition or vain conceit. Rather, in humility value others above yourselves” (Philippians 2:3). However, the vast majority of the psychological research finds that Christians are not humble at all.

Most of the studies included in the Koenig review are correlational. Psychologists usually measure the degree of someone’s religious belief, or their “religiosity,” by asking them how important religion is to them, or how often they attend church services or pray. Then this religiosity score gets correlated with different outcomes. Correlational studies are ineffective at establishing causality. Does Christianity make someone optimistic or do optimists tend to become Christians?

Some of the studies in the review use a clinical trial or experimental design, and these establish that Christian belief indeed causes changes in psychology. For example, Koenig found 30 such studies on the effect of Christian belief on depression. The large majority established that Christian belief alleviates depression. As an example, one of these studies measured the effect of incorporating religious content into depression therapy with religious patients. As predicted, therapy with religious content was more effective for religious depressives than non-religious therapy.

Religious conversion is a kind of natural experiment on the effect of religion. If Christianity causes well-being, you would expect people’s well-being to increase after they converted to Christianity. This is just what you do find: people who convert to Christianity report that conversion was preceded by a period of high stress and feelings of inadequacy and limitation. Conversion brings them a greater sense of adequacy, competence, self-esteem, and self-confidence.

Christian self-enhancement

So far we have seen that Christian doctrine seems designed to bolster positive illusions and that Christian belief and positive illusions lead to many of the same outcomes. There is also research that shows that Christian religiosity is correlated with self-enhancement.

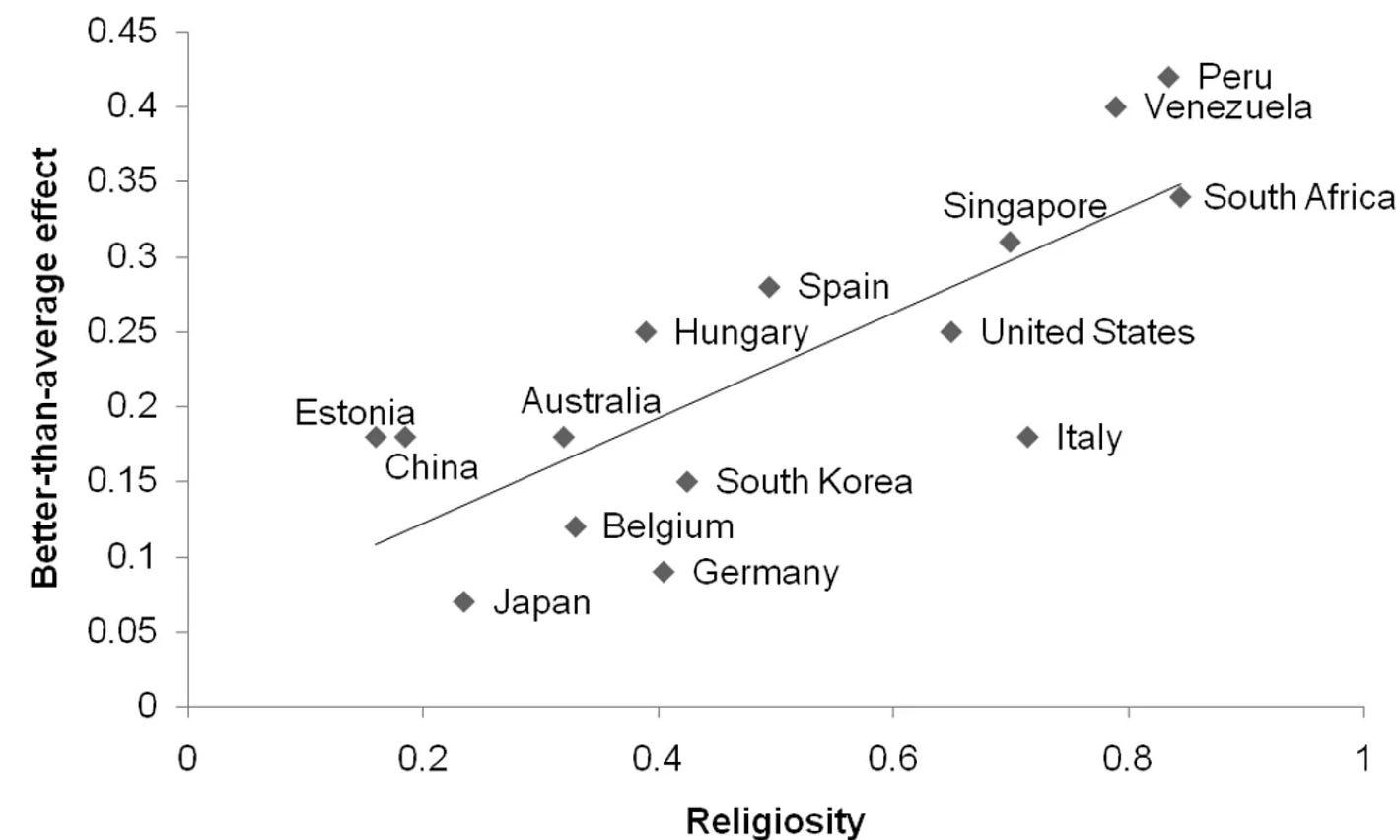

One measure of self-enhancement is the better than average effect. If you asked people to rank their positive traits on a scale of 1 to 10, and they responded realistically, the average score would usually be around 5. If the score is much higher, the reason is likely to be that people are enhancing their positive traits: the average person believes themselves to be better than average. The better than average effect appears to be particularly strong among Christians. Kimmo Eriksson and Alexander Funcke correlated scores on a self-evaluation test with the religiosity of countries and found an extremely strong correlation of 0.78 between religiosity and the better than average effect. The effect was driven largely by high self-enhancement in heavily Christian nations like Peru, Venezuela, and South Africa and low scores in secular places like China and Northern Europe, where people seem to have a more realistic self-image.

Psychologists distinguish between agentic and communal traits. Agentic traits like intelligence, competence, and leadership relate to the ability to impose one’s will on the world. Communal traits like agreeableness, helpfulness, empathy, and altruism relate to the ability to build and maintain community. Eriksson and Funcke found, as others have, that Christians are particularly prone to exaggerate their communal traits and are not much different from the average on agentic trait exaggeration.

A meta-analysis found that there was a positive relationship between Christian religiosity and self-enhancement. Christians scored particularly high on impression management, which means that their self-deceptive beliefs are geared towards making others think well of them. Sample items gauging impression management are:

I never cover up my mistakes.

I have never dropped litter on the street.

When I was young I sometimes stole things.

People who strongly deny that they sometimes cover up mistakes or that they stole as children are very likely being dishonest both with themselves and with other people, and Christians seem prone to this kind of dishonesty.

Christians are also prone to claim to know things that they don’t. Jochen E. Gebauer and colleagues studied how religiosity related to knowledge overclaiming.2 In overclaiming tests, participants are given a list and asked how many terms they recognize. The catch is that many of the terms are made up, so people who claim to recognize those terms are pretending to know things that they don’t. The original version of this test measured overclaiming on scientific knowledge. Legitimate scientific terms like “asteroid” and “nuclear fusion” were mixed in with bogus terms like “ultra-lipid” and “plates of parallax.” People who claimed to be familiar with the bogus terms also scored high on measures of self-enhancement.

Gebauer et al. invented their own tests to measure the extent of Christian knowledge overclaiming. One test measured overclaiming on topics like science and finance, which are not strongly related to Christian identity. They also tested overclaiming on topics related to establishing and maintaining community, like charity and childcare, and on knowledge of Christian scripture and theology. The psychologists’ prediction was that Christian religiosity would correlate most strongly with overclaiming on communal and Christian knowledge, as Christians pride themselves on this type of knowledge. In the overclaiming tests, fake charities and Bible stories, like “Asch AIDS Aid” and “Jesus rejects the golden goblet,” were mixed in with real ones. Religiosity turned out to predict overclaiming of all sorts, but particularly of communal and Christian knowledge.

In another study, Gebauer and colleagues constructed the Communal Narcissism Inventory to measure self-enhancement on communal traits, like agreeableness, helpfulness, and empathy. Some items on the scale include:

I am the most helpful person I know.

I am going to bring peace and justice to the world.

I am the best friend someone can have.

I will be well known for the good deeds I will have done.

People who strongly agree with these items very likely have an unrealistic self-image, as most people are not, in fact, the best friend that someone can have, let alone the savior who brings peace and justice to the world.

Gebauer et al. found that scores on the scale were unrelated or negatively related to actual communal traits. A knowledge overclaiming task found that those scoring very high in communal self-enhancement were likely to overclaim knowledge about charities and parenting, but did not possess deeper knowledge of those topics than the average subject. Communal self-enhancers were also rated as lower in actual communal traits by other people. That is to say, even though communal self-enhancers believed that they were very empathetic and helpful, people who knew them perceived them as disagreeable, lazy, and unhelpful. Gebauer and colleagues also found that Christian religiosity is correlated with communal self-enhancement.

The relationships between Christian religiosity, self-enhancement, and self-esteem are stronger in more Christian than in more secular countries. For this reason, these relationships are stronger in the USA, where 51% believe in God as described in the Christian scriptures, than they are in the UK or the former East Germany, where only 27% and 21% do. In the Gebauer et al. study discussed above, the relationship between religiosity and communal self-enhancement was much stronger in the USA (r=0.34) than it was in the UK (r=0.13) and East Germany (r=0.12).3 You find the same pattern when you look at the relationship between religiosity and self-esteem. Gebauer et al. believe that in places where Christianity is highly popular, Christians gain greater social acceptance and value because of their beliefs. Since social value generates self-esteem, the self-esteem of Christians is higher in more heavily Christian places. Since high self-esteem people tend to self-enhance more, self-enhancement is also more strongly correlated with religiosity in heavily Christian places.

Convergent lines of evidence establish that one of the functions of Christian belief is to bolster positive illusions. Not only does Christian doctrine intuitively seem designed to instill these illusions, but Christian belief has the same effects that illusions do. Also, Christian religiosity is strongly related to self-enhancement.

The psychological studies that I have reviewed here suggest that Christians tend to be dishonest with themselves and others. They claim to know things that they don’t and deny their susceptibility to universal human weaknesses and failings. They are likely to agree with statements that imply a grandiose self-image, like “I am going to bring peace and justice to the world” and “I will be well known for the good deeds that I have done.” Also, while Christians commonly tell others that they are humble, there is no evidence that they are. Christians tend to be profoundly convinced that they are better than average, especially on traits that are central to Christian identity, like empathy and altruism.

In my last essay, I distinguished between functional and dysfunctional illusions. Positive illusions are life-enhancing when their holders are capable of adjusting them to reality, but can also lead to a delusional self-image and denial of reality.

One way of interpreting the evidence is that Christian beliefs are usually functional, but become dysfunctional in highly religious Christians. Moderate belief, tempered by realism, results in self-esteem, well-being, coping skills, optimism, and other psychological benefits. However, strongly religious Christians are prone to dysfunctional communal narcissism. These are the type of people who believe themselves to be highly empathetic and altruistic, but are rated as lazy and unhelpful by those who know them. The problem of Christian communal narcissism is likely to be particularly strong in the USA and other nations where Christianity is prevalent and respected.

The world’s 2.6 billion Christians have massive power for good or ill. The positive illusions theory of Christianity is a tool that citizens, scientists, writers, and policy makers can use to better understand this behemoth and steer it in the right direction.

This book is also for free available at Everand. Pages are from the Kindle edition.

See Figure 3 on p. 67 of Christian Self-Enhancement.

Really interesting and insightful -- worth considering than the same traits can be helpful or harmful in different context -- perhaps this follows from your discussion of thing being different in USA than in other places.

I will make the case that illusions are necessary for developing a coherent self. Keep an eye out for it next week.